Statins

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton and Mason Trauger

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Statin medications are a class of lipid-lowering medications that decrease illness and mortality in those who are at high risk of cardiovascular disease, being the most common cholesterol-lowering drugs.[1]

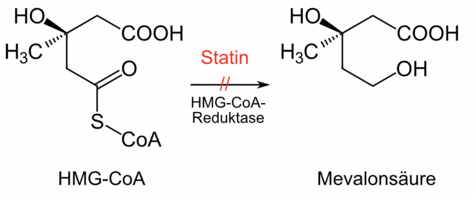

- Statins are 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA Reductase) inhibitors. Statins competitively inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, which limits the rate of cholesterol synthesis (primarily in the liver). As a result, statins break down LDL, decrease the synthesis of VLDL, and increase HDL. Through this mechanism, statins can reduce the amount of plaque that forms in the arteries (see Atherosclerosis for more information).[2]

- Statins may also inhibit many of the structural and functional components of the arteriosclerotic process. Structural effects include reductions in vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy and proliferation, fibrin deposition, and collagen cross-linking. Among the functional effects are improvements in endothelial function, vasodilation due to increased nitric oxide production, reduction in inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, and down-regulation of angiotensin II and endothelin receptors.[3]

There are several different types of statins. The main difference between them is their potency.

Uses[edit | edit source]

Clinicians use statin medications for the treatment of:

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Hyperlipoproteinemia

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Hyperlipidemia

- Atherosclerosis

- Myocardial infarction prophylaxis

- Stroke prophylaxis [1] [2]

Brief Literature Review[edit | edit source]

- A 2019 systematic review and network meta-analysis compared the benefits and harms of statins in secondary prevention for patients with ischemic stroke. The resultant conclusion suggests statins are no better than placebo in preventing all strokes and all-cause mortality, but reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic strokes and other cardiovascular events if a patient had a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack.[4]

- A 2018 systematic review with meta-analysis suggests that more intensive pharmacotherapeutic LDL-C lowering (via statin dosage) was associated with a greater reduction in risk of total and cardiovascular mortality compared to less intensive LDL-C lowering. This effect is related to the individual's baseline LDL-C level, as there was no significant difference when LDL-C was less than 100 mg/dL at baseline.[5]

- A 2022 statement from the United States Preventive Task Force recommends the prescription of a statin for the primary prevention of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) in adults aged 40 to 75 years who have at least 1 CVD risk factor (dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking), and an estimated 10-year CVD risk of 10+%.[6]

Adverse Effects[edit | edit source]

Statins are usually well-tolerated, with myositis, rhabdomyolysis, hepatotoxicity, and diabetes mellitus being the most common adverse reactions.

- Statin-associated muscle symptoms may present as diffuse myalgias or otherwise unexplainable muscle tenderness or weakness. Of all statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), myalgia is the most common, affecting 5-10% of users. These symptoms are generally dose dependent, and resolve upon discontinuation of medication.[7]

- Rhabdomyolysis is the most serious complication of statin use, but its occurrence is rare (current incidence rate of 1 case per 10,000 person-years of treatment after market removal of cerivastatin).[7]

- Statin-associated immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy(IMNM) can occur due to the development of antibodies against the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme. Symmetrical, proximal muscle weakness with significantly increased creatine phosphokinase (CPK) that continues for months after ceasing statins is common in IMNM.[1]

A notable adverse event occurs when consuming grapefruit juice while taking statins. Grapefruit juice increases the systemic concentrations of statins, thus increasing the risk of all side effects, including all SAMS (particularly myalgia), liver damage, and kidney failure.[7]

Smoking cigarettes should also be avoided when taking statins. Smoking decreases the positive effects of statins. Smokers had a 74 to 86 % higher risk of events.[8]

Physiotherapy Implications[edit | edit source]

Statins may increase the incidence of exercise-related muscle complaints and in some studies augment the exercise-induced rise in muscle enzymes, but statins do not consistently reduce muscle strength, endurance, overall exercise performance or physical activity.[9]

When lab values are available, monitoring Creatine Phosphokinase (CK or CPK) can be useful to identify clinical rhabdomyolysis. Although SAMS can occur without an increase in CK, certain health organizations categorize SAMS based on CK elevation.[7] See our page on Rhabdomyolysis and a rhabdomyolysis case study for effective management of patients with this condition.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sizar O, Khare S, Jamil RT, Talati R. Statin medications. StatPearls [Internet]. 2024. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430940/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bansal AB, Cassagnol M. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors. StatPearls [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542212/

- ↑ Mangat S, Agarwal S, Rosendorff C. Do statins lower blood pressure?. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 2007 Jun;12(2):112-23.Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1074248407300380(accessed 9.4.2022)

- ↑ Tramacere I, Boncoraglio GB, Banzi R, Del Giovane C, Kwag KH, Squizzato A, Moja L. Comparison of statins for secondary prevention in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019 Mar 26;17(1):67.

- ↑ Navarese EP, Robinson JG, Kowalewski M, Kolodziejczak M, Andreotti F, Bliden K, Tantry U, Kubica J, Raggi P, Gurbel PA. Association Between Baseline LDL-C Level and Total and Cardiovascular Mortality After LDL-C Lowering: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018 Apr 17;319(15):1566-1579.

- ↑ US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Chelmow D, Coker TR, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Jaén CR, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Pbert L, Ruiz JM, Stevermer J, Wong JB. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2022 Aug 23;328(8):746-753.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Thompson PD, Panza G, Zaleski A, Taylor B. Statin-Associated Side Effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 May 24;67(20):2395-2410.

- ↑ Milionis HJ, Rizos E, Mikhailidis DP. Smoking diminishes the beneficial effect of statins: observations from the landmark trials. Angiology. 2001 Sep;52(9):575-87.

- ↑ Noyes AM, Thompson PD. The effects of statins on exercise and physical activity. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2017 Sep 1;11(5):1134-44.